Airborne Artillery

Received this in an email from old army mate Stoney B. I couldn’t find a link so have included the entire text for the interest of readers and also in the interest of winding up any peaceniks who might accidently arrive on my site.

Boeing’s new laser cannon can melt a hole in a tank from five miles away and 10,000 feet up-and it’s ready to fly this year

Creating a laser that can melt a soda can in a lab is a finicky enough task. Later this year, scientists will put a 40,000-pound chemical laser in the belly of a gunship flying at 300 mph and take aim at targets as far away as five miles. And we’re not talking aluminum cans. Boeing’s new Advanced Tactical Laser will cook trucks, tanks, radio stations-the kinds of things hit with missiles and rockets today. Whereas conventional projectiles can lose sight of their target and be shot down or deflected, the ATL moves at the speed of light and can strike several targets in rapid succession.

Last December, Boeing, under contract from the Department of Defense, installed a $200-million prototype of the laser into a C-130 at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico in preparation for test flights this year. From there it will go to the Air Force for more testing, and it could be in battle within five years.

Precise control over the beam’s aim allows it to hit a moving target a few inches wide and confine the damage to that space. The Pentagon hopes such precision will translate into less collateral damage than even today’s most accurate missiles. Future versions using different types of lasers could be mounted on smaller vehicles, such as fighter jets, helicopters and trucks.

How to Melt a Tank in Three Seconds Or Less

1. Find Your Target

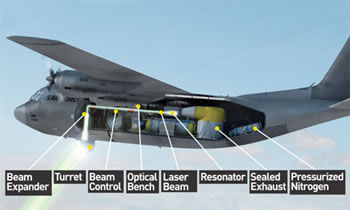

When the C-130 flies within targeting range (up to five miles away), the gunner aims using a rotating video camera mounted beneath the fuselage. The computer locks onto the object to continually track it. A second crew member precisely adjusts the laser beam’s strength -higher power to disable vehicles, lower power to knock out, say, a small power generator. The gunner hits ‘fire,’ and the computer takes over from there.

2. Heat Up the Laser

In a fraction of a second, chlorine gas mixes with hydrogen peroxide. The resulting chemical reaction creates highly energetic oxygen molecules. Pressurized nitrogen pushes the oxygen through a fine mist of iodine, transferring the oxygen’s energy to iodine molecules, which shed it in the form of intense light.

3. Amplify the Beam

The optical resonator bounces this light between mirrors, forcing more iodine molecules to cough up their photons, further increasing the laser beam’s intensity. From there, the light travels through a sealed pipe above the weapon’s crew station and into a chamber called the optical bench. There, sensors determine the beam’s quality, while mechanically controlled mirrors compensate for movement of the airplane, vibration and atmospheric conditions. Precise airflow regulates the chamber’s temperature and humidity, which helps keep the beam strong.

4. Stand Clear

A kind of reverse telescope called the beam expander inside a retractable, swiveling pod called the turret widens the beam to 20 inches and aims it. The laser’s computer determines the distance to the target and adjusts the beam so it condenses into a focused point at just the right spot. Tracking computers help make microscopic adjustments to compensate for both the airplane’s and the target’s movement. A burst of a few seconds’ duration will burn a several-inch-wide hole in whatever it hits.

F A Q

• How hot is the beam? The laser itself isn’t hot, but it can heat its target to thousands of degrees.

• Does the laser sear everything in its path? Yes If a bird flew into the firing laser’s line of sight-

well, no more bird. Fortunately, the weapon will fire for only a few seconds at a time, minimizing the risk.

• Does it melt its target or just set it aflame? That depends on what it hits. It will melt metal, but if the target is combustible, it will burn.

Creating a laser that can melt a soda can in a lab is a finicky enough task. Later this year, scientists will put a 40,000-pound chemical laser in the belly of a gunship flying at 300 mph and take aim at targets as far away as five miles. And we’re not talking aluminum cans. Boeing’s new Advanced Tactical Laser will cook trucks, tanks, radio stations-the kinds of things hit with missiles and rockets today. Whereas conventional projectiles can lose sight of their target and be shot down or deflected, the ATL moves at the speed of light and can strike several targets in rapid succession.

Last December, Boeing, under contract from the Department of Defense, installed a $200-million prototype of the laser into a C-130 at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico in preparation for test flights this year. From there it will go to the Air Force for more testing, and it could be in battle within five years.

Precise control over the beam’s aim allows it to hit a moving target a few inches wide and confine the damage to that space. The Pentagon hopes such precision will translate into less collateral damage than even today’s most accurate missiles. Future versions using different types of lasers could be mounted on smaller vehicles, such as fighter jets, helicopters and trucks.

How to Melt a Tank in Three Seconds Or Less

1. Find Your Target

When the C-130 flies within targeting range (up to five miles away), the gunner aims using a rotating video camera mounted beneath the fuselage. The computer locks onto the object to continually track it. A second crew member precisely adjusts the laser beam’s strength -higher power to disable vehicles, lower power to knock out, say, a small power generator. The gunner hits ‘fire,’ and the computer takes over from there.

2. Heat Up the Laser

In a fraction of a second, chlorine gas mixes with hydrogen peroxide. The resulting chemical reaction creates highly energetic oxygen molecules. Pressurized nitrogen pushes the oxygen through a fine mist of iodine, transferring the oxygen’s energy to iodine molecules, which shed it in the form of intense light.

3. Amplify the Beam

The optical resonator bounces this light between mirrors, forcing more iodine molecules to cough up their photons, further increasing the laser beam’s intensity. From there, the light travels through a sealed pipe above the weapon’s crew station and into a chamber called the optical bench. There, sensors determine the beam’s quality, while mechanically controlled mirrors compensate for movement of the airplane, vibration and atmospheric conditions. Precise airflow regulates the chamber’s temperature and humidity, which helps keep the beam strong.

4. Stand Clear

A kind of reverse telescope called the beam expander inside a retractable, swiveling pod called the turret widens the beam to 20 inches and aims it. The laser’s computer determines the distance to the target and adjusts the beam so it condenses into a focused point at just the right spot. Tracking computers help make microscopic adjustments to compensate for both the airplane’s and the target’s movement. A burst of a few seconds’ duration will burn a several-inch-wide hole in whatever it hits.

F A Q

• How hot is the beam? The laser itself isn’t hot, but it can heat its target to thousands of degrees.

• Does the laser sear everything in its path? Yes If a bird flew into the firing laser’s line of sight-

well, no more bird. Fortunately, the weapon will fire for only a few seconds at a time, minimizing the risk.

• Does it melt its target or just set it aflame? That depends on what it hits. It will melt metal, but if the target is combustible, it will burn.

Creating a laser that can melt a soda can in a lab is a finicky enough task. Later this year, scientists will put a 40,000-pound chemical laser in the belly of a gunship flying at 300 mph and take aim at targets as far away as five miles. And we’re not talking aluminum cans. Boeing’s new Advanced Tactical Laser will cook trucks, tanks, radio stations-the kinds of things hit with missiles and rockets today. Whereas conventional projectiles can lose sight of their target and be shot down or deflected, the ATL moves at the speed of light and can strike several targets in rapid succession.

Last December, Boeing, under contract from the Department of Defense, installed a $200-million prototype of the laser into a C-130 at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico in preparation for test flights this year. From there it will go to the Air Force for more testing, and it could be in battle within five years.

Precise control over the beam’s aim allows it to hit a moving target a few inches wide and confine the damage to that space. The Pentagon hopes such precision will translate into less collateral damage than even today’s most accurate missiles. Future versions using different types of lasers could be mounted on smaller vehicles, such as fighter jets, helicopters and trucks.

How to Melt a Tank in Three Seconds Or Less

1. Find Your Target

When the C-130 flies within targeting range (up to five miles away), the gunner aims using a rotating video camera mounted beneath the fuselage. The computer locks onto the object to continually track it. A second crew member precisely adjusts the laser beam’s strength -higher power to disable vehicles, lower power to knock out, say, a small power generator. The gunner hits ‘fire,’ and the computer takes over from there.

2. Heat Up the Laser

In a fraction of a second, chlorine gas mixes with hydrogen peroxide. The resulting chemical reaction creates highly energetic oxygen molecules. Pressurized nitrogen pushes the oxygen through a fine mist of iodine, transferring the oxygen’s energy to iodine molecules, which shed it in the form of intense light.

3. Amplify the Beam

The optical resonator bounces this light between mirrors, forcing more iodine molecules to cough up their photons, further increasing the laser beam’s intensity. From there, the light travels through a sealed pipe above the weapon’s crew station and into a chamber called the optical bench. There, sensors determine the beam’s quality, while mechanically controlled mirrors compensate for movement of the airplane, vibration and atmospheric conditions. Precise airflow regulates the chamber’s temperature and humidity, which helps keep the beam strong.

4. Stand Clear

A kind of reverse telescope called the beam expander inside a retractable, swiveling pod called the turret widens the beam to 20 inches and aims it. The laser’s computer determines the distance to the target and adjusts the beam so it condenses into a focused point at just the right spot. Tracking computers help make microscopic adjustments to compensate for both the airplane’s and the target’s movement. A burst of a few seconds’ duration will burn a several-inch-wide hole in whatever it hits.

F A Q

• How hot is the beam? The laser itself isn’t hot, but it can heat its target to thousands of degrees.

• Does the laser sear everything in its path? Yes If a bird flew into the firing laser’s line of sight-

well, no more bird. Fortunately, the weapon will fire for only a few seconds at a time, minimizing the risk.

• Does it melt its target or just set it aflame? That depends on what it hits. It will melt metal, but if the target is combustible, it will burn.

Creating a laser that can melt a soda can in a lab is a finicky enough task. Later this year, scientists will put a 40,000-pound chemical laser in the belly of a gunship flying at 300 mph and take aim at targets as far away as five miles. And we’re not talking aluminum cans. Boeing’s new Advanced Tactical Laser will cook trucks, tanks, radio stations-the kinds of things hit with missiles and rockets today. Whereas conventional projectiles can lose sight of their target and be shot down or deflected, the ATL moves at the speed of light and can strike several targets in rapid succession.

Last December, Boeing, under contract from the Department of Defense, installed a $200-million prototype of the laser into a C-130 at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico in preparation for test flights this year. From there it will go to the Air Force for more testing, and it could be in battle within five years.

Precise control over the beam’s aim allows it to hit a moving target a few inches wide and confine the damage to that space. The Pentagon hopes such precision will translate into less collateral damage than even today’s most accurate missiles. Future versions using different types of lasers could be mounted on smaller vehicles, such as fighter jets, helicopters and trucks.

How to Melt a Tank in Three Seconds Or Less

1. Find Your Target

When the C-130 flies within targeting range (up to five miles away), the gunner aims using a rotating video camera mounted beneath the fuselage. The computer locks onto the object to continually track it. A second crew member precisely adjusts the laser beam’s strength -higher power to disable vehicles, lower power to knock out, say, a small power generator. The gunner hits ‘fire,’ and the computer takes over from there.

2. Heat Up the Laser

In a fraction of a second, chlorine gas mixes with hydrogen peroxide. The resulting chemical reaction creates highly energetic oxygen molecules. Pressurized nitrogen pushes the oxygen through a fine mist of iodine, transferring the oxygen’s energy to iodine molecules, which shed it in the form of intense light.

3. Amplify the Beam

The optical resonator bounces this light between mirrors, forcing more iodine molecules to cough up their photons, further increasing the laser beam’s intensity. From there, the light travels through a sealed pipe above the weapon’s crew station and into a chamber called the optical bench. There, sensors determine the beam’s quality, while mechanically controlled mirrors compensate for movement of the airplane, vibration and atmospheric conditions. Precise airflow regulates the chamber’s temperature and humidity, which helps keep the beam strong.

4. Stand Clear

A kind of reverse telescope called the beam expander inside a retractable, swiveling pod called the turret widens the beam to 20 inches and aims it. The laser’s computer determines the distance to the target and adjusts the beam so it condenses into a focused point at just the right spot. Tracking computers help make microscopic adjustments to compensate for both the airplane’s and the target’s movement. A burst of a few seconds’ duration will burn a several-inch-wide hole in whatever it hits.

F A Q

• How hot is the beam? The laser itself isn’t hot, but it can heat its target to thousands of degrees.

• Does the laser sear everything in its path? Yes If a bird flew into the firing laser’s line of sight-

well, no more bird. Fortunately, the weapon will fire for only a few seconds at a time, minimizing the risk.

• Does it melt its target or just set it aflame? That depends on what it hits. It will melt metal, but if the target is combustible, it will burn.

The thing that should be worrying the USAF (and anyone looking at spending 15 billion dollars on strike a/c soon) is what happens if you mount it on a truck and shoot it a planes.

The day of the bomber may well be coming to an end.

I figure they should always develop the defence at the same time as the weapon. Time will tell if they have.

Wonder Woman’s plane was invisible so the beam would go straight through ;-P

Given the rapid advancement in UAVs, (witness the RAF flying them over Afghanistan from a control center in Nevada) future employment as a pilot in the USAF or any other air force is likely to be restricted to driving cargo around.

Attack and fighter aircraft are likely to be piloted by people far removed from any threat.

I can see a time in the not too distant future where small hypersonic UAVs take off from bases or ships or are dropped from ‘mother ships’ around the world then zip to trouble spots in minutes, deliver a nasty projectile of some form and flit away whilst the ‘pilot’ listens to his/her IPOD in a comfy bunker on the other side of the world.

If it was a long mission, say loitering over a ground force to provide protection or surveillance, pilots could (do now) work in shifts. It sounds silly, even far fetched today, but you could see a pilot knock off half way through a mission and catch a tram home in time to watch the ‘battle’ on the evening news.

After a good night’s sleep he could be back in front of his computer screens and joystick ready to take over the mission again still thinking about the eggs and bacon his missus whipped up that morning.

Too far-fetched some might say, however the pace of change can be extraordinary. My father started his career in the RAF on a single engined, 160 Km an hour bi-plane known as a Hawker Demon (in Iraq) and finished working for strike command deep underground in Buckinghamshire with it’s fleet of nuclear armed ‘V Bombers’ able to strike across the globe.

In the span of one man’s career, military aviation went from doped fabric and wooden struts between upper and lower wings to swing-wing super-sonic Tornadoes.

It boggles my mind when I think of the institutional and technological changes he had to adapt to during his time in uniform, including service in North Africa and the invasion of Europe during the second world war.

He’s still alive and kicking, well shuffling, and takes a keen interest in stories from Fallujah and Habbaniya as his Iraq posting during the 1930s meant he spent time at both places.